School has come a long way since the 19th and 20th centuries. From corporal punishment to lunch to walking five miles in the snow just to get there, here are just a few ways school was different a century ago, adapted from an episode of The List Show on YouTube.

One hundred years ago, many kids had jobs, whether on family farms or at mills or factories—which meant that regular 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. school hours wouldn't work. Some children attended elementary and high school at night [PDF], and in some cities, it was mandatory to provide night school for children.

In 1900, just 51 percent of people between the ages of 5 and 19 were enrolled in school. That changed quickly, becoming 75 percent by 1940 [PDF], likely due to factors including education reform and child labor laws.

There have been what are essentially high schools in the U.S. ever since what’s now known as the Boston Latin School was founded in 1635, but high school attendance was particularly low 100 years ago. In 1900, about 11 percent of 14-to-17-year-olds attended high school; by 1920, things hadn’t changed much: According to an analysis done by the National Center for Education Statistics, the “median years of school completed by persons age 25 and over” at that time was 8.2 years.

In rural areas in the U.S., there was usually a single school with a single room where one teacher handled every kid in grades one through eight. They sat in order of age, with the youngest up front and the oldest in the back. Cities, however, had bigger schools with multiple classrooms [PDF].

Nowadays, most states require a minimum of 180 days of instruction per year in public schools, but in 1905, the average school had just 151 days. Children typically missed more days of school back then, too: The average student attended only 106 days per year. Kids who worked on farms, in particular, took a lot of absences. They would usually take the spring and autumn off to work.

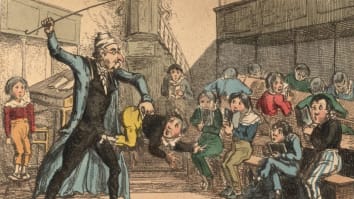

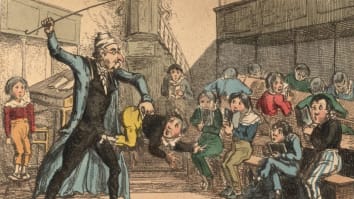

In the 1900s, it wasn’t unusual for teachers to dole out corporal punishment. The Board of Education in Franklin, Ohio, laid out its rules in 1883 [PDF], which included this: “Pupils may be detained at any recess or not exceeding fifteen minutes after the hour for closing the afternoon session, when the teacher deems such detention necessary, for the commitment of lessons or for the enforcement of discipline … Whenever it shall become necessary for teachers to resort to corporal punishment, the same shall not be inflicted upon head or hands of the pupil.”

Other school systems allowed teachers more freedom [PDF]. They were known to hit students’ knuckles with a ruler along with conducting other forms of punishment, like having a child write a single phrase over and over again.

Sometimes, if a child got in trouble, a teacher would put a pointy cap on their head known as a Dunce cap and have them sit in the corner of the room. (According to 19th century accounts, the caps occasionally featured bells to add extra shame.) Some remember it still being used as a punishment well into the 1950s.

It’s commonly reported that the dunce cap came from John Duns Scotus, a religious philosopher born in the 13th century. He gained a following of people who would come to be called “dunces” and supposedly wore pointy hats; Scotus thought that the hats allowed for knowledge to be funnelled into the brain. It's said that eventually, his teachings fell out of favor, and both the word and the cap took on a negative connotation. Sadly, evidence for this theory about the origin of the hats is lacking.

Around 1919, about 84 percent of teachers were women. Compare that with the year 1800, when 90 percent of teachers were men. It became a career path primarily for women when public education boomed during the mid-1800s. Basically, education reformers wanted to show that the system could be cheap, so they filled the new teaching jobs with women, who were paid much less than men.

Girls were pushed toward home economics and classes that focused on domestic skills. In some places, girls weren’t even allowed to enter school through the same door as boys.

The schools that white children attended were much better funded than the schools for Black children, which often used old books and supplies that white schools had gotten rid of, and teachers in the two systems experienced a major pay disparity. In 1954, segregation of schools was ruled unconstitutional, but true equity remains a problem for education reformers today.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, children in classrooms were beginning to learn and recite the Pledge of Allegiance, which was written by a man named Francis Bellamy when he worked in a magazine marketing department in 1892. The original words were simply: “I pledge allegiance to my flag and the republic for which it stands; one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

In every subject from writing to arithmetic, the expectation was that students would memorize and recite the important components of the lessons. Homework mostly entailed practicing that memorization. Here’s a selection from McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers, a textbook that was often memorized at the time: “This is a fat hen. The hen has a nest in the box. She has eggs in the nest. A cat sees the nest, and can get the eggs.”

It was led by reformers like John Dewey and Ella Flagg Young. As the first female superintendent of the school system in a major American city (Chicago), Young focused on teacher training and empowerment, in addition to her writings on educational theory. These philosophers and educators encouraged a shift in focus from forcing children to memorize to empowering them with more options. They wanted the classroom to be communal and democratic rather than all about a teacher up front telling kids what to do.

The progressives' vision never fully became a reality, but schools did implement parts of it. One interesting attempt occurred in Gary, Indiana, where schools were turned into microcosms of communities. Students were expected to apply the practical skills they were learning to help keep schools running. This could include cooking and serving lunch to their classmates, building their own desks, or even handling plumbing and electrical work in school buildings (with supervision, of course).

One hundred years ago, music classes in public schools usually involved teaching music theory, singing, or instruments. (This meant the "normal schools" that trained teachers also had mandatory music courses.) Luckily for the eardrums of early 20th century parents, the recorder didn’t become the standard starter instrument until the mid-20th century. Kids in 1919 also weren’t singing “50 Nifty United States,” because it wasn’t written until the 1960s. But they were singing songs like "A Cat-Land Law," "Looby Looby," "Song of the Noisy Children," and "Dollies’ Washing Day."

German gymnastics and Swedish gymnastics were two of the most popular styles of PE (or PC) used at the time. The former involved lifting weights, using balance beams, climbing ladders and ropes, and doing some cardio like running. The Swedish style sometimes made use of similar equipment, but was more focused on simple whole-body exercises and had a more organized method, with an adult delivering instructions, going from easy movements to challenging ones over the course of the class. As the 20th century began, gym classes also started incorporating lessons on hygiene and health.

Unfortunately, little research has been done into the history of recess, but we do know that by 1919, many popular playground games had been invented, like jacks, red rover, hopscotch, and kickball. Kickball was actually just emerging in the U.S., coming out of Cincinnati in 1917.

School lunch programs started appearing in cities like Philadelphia and Boston in the early 1900s. By the early 1920s, many schools had followed suit and provided hot food like soups.

But it wasn’t quite like what we have today: No visits to Target, no Minions backpacks or Trapper Keepers. One 1924 ad from a Montana store urged parents to let kids do the shopping themselves, saying, “Train the children to do their own buying economically and in good taste. They are safe to shop here because we will make exchanges or refund their money if their selections are not entirely approved at home.”

Kids in classrooms did most of their work with a slate and a piece of chalk, because paper and ink were expensive. There was typically a blackboard in the front of the room as well. Blackboards began to be manufactured around the 1840s. A Scottish teacher named James Pillans is often cited as the inventor of the blackboard. In the early 1800s, he supposedly connected a bunch of individual slates together to make one big enough for the maps in his geography classes.

Kids were expected to get to school by any means possible, which could have meant hitching a ride on a wagon, carriage, or cart. The modern idea of school buses started emerging in the first decades of the 20th century. By the early 1930s, there were around 63,000 of them in the United States.

For example, Nebraska passed a law in 1919 that meant that no one could teach a foreign language before they “successfully passed the eighth grade.” Iowa had a similar law. And because World War I had just ended, even states without English-only laws on the books removed German classes from their schools. In 1923, the Supreme Court ruled that these laws were unconstitutional.